0 Comments

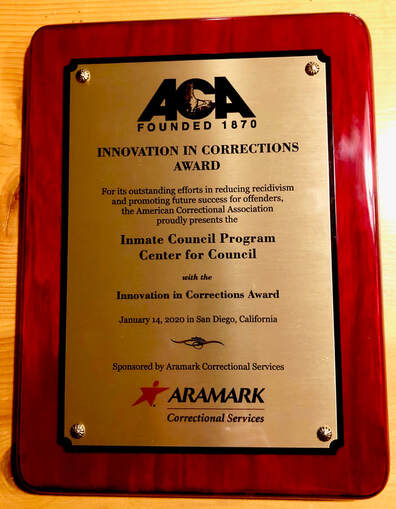

My name is Efrain Ortiz. I am the Program Assistant with Center for Council, but most importantly I am an example of what transpires when one engages in the practice of council. I believe in life you don’t merely stumble across opportunities by chance. I was first introduced to council while serving a 12-year sentence inside of California State Prison-Los Angeles County, in Lancaster, California, where I worked as a clerical assistant in the main office. I was in charge of typing up incidents and rules violation reports. I already had my share of violent experiences, but working inside the main office I got to witness how violent and disruptive prison really is, as I had a firsthand view of every violent incident which took place in our facility. Our yard was one of the most violent, high-security facilities in the state of California at the time. We lacked resources and support with only two self-help groups (Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous) which rotated every Saturday, until Center for Council came along. It was here, in the circle created by Center for Council, where we as individuals had the opportunity to sit amongst other men and both speak and be heard with regard. We learned the four intentions of council: speak from the heart, to speak from that sacred place where often I wouldn’t share with just anyone; listen from the heart, something I continue to work on as it is often times the forgotten half of true communication, holding my judgement or my need to resolve; be spontaneous, allowing yourself to say what arises at the given moment that the talking peace is in your hand; be lean, so others have a chance to share their stories, and I found that often I learned more about myself through the stories of others. To be able to get to this point was no easy task. I was sitting in a high security, level four prison with men who have committed some horrible crimes. But in the council circle, I was no longer sitting with those boys from back then. Through practice, we began to trust each other as the stories got deeper, the layers we began to peel off revealed the hurt we suppressed for many years. We began to connect to one another through our shared stories, as we connected the dots to our past, understanding those traumatic experiences and how they led us to a tumultuous life. The amazing thing was, we started to look at one another as human instead of by race, gang affiliation or moniker.  The American Correctional Association has awarded Center for Council's Inmate Council Program its 2019 "Innovation in Corrections Award." This prestigious award honors the powerful work C4C has done building programming for the state's incarcerated population, now reaching 22 of the state's 35 prison facilities. The Inmate Council Program is a six-month intervention where participating inmates are trained to facilitate Council sessions for their peers, empowering them to become positive agents of change, on the prison yard, and in their lives. The program contributes to a shift of culture within prisons and equips participants with tools for successful reentry and reintegration into their communities upon release The award was presented on January 14, 2020, in a ceremony at the end of ACA's Convention. The award was presented to Center for Council "For its outstanding efforts in reducing recidivism and promoting future success for offenders" and was accepted by Sam Escobar and Jared Seide. ACA President, Gary Rohr, and Chair of the Awards Committee, Vicki Myers, presented Sam and Jared with the award. The American Correctional Association is the oldest association developed specifically for practitioners in the correctional profession. The ACA provides a professional organization for individuals and groups committed to improving the justice system. The annual "Innovations is Correction Award" is intended to broaden the knowledge and familiarity amongst the membership of the ACA of successful rehabilitative program interventions and to recognize an outstanding correctional program.  A wide-ranging new study, led by Principle Investigator Dr. Stacy Calhoun, of the University of California Los Angeles, has found that Center for Council's statewide Inmate Council Program demonstrated "significantly positive outcomes" for the subjects involved in the study. This study involved 399 inmates participating in ICP groups throughout eight different facilities, and examined quantitative measures, as well as qualitative assessments of program impact. The study looked at factors including changes in physical and verbal aggression, anger, hostility and PTSD symptomatology and found notable decreases in those areas, among inmates who participated in the program. The study also found statistically significant increases in measures of resilience, empathy, mindfulness and social connectedness. Dr. Calhoun's report states that "findings from this evaluation suggest that this program is having a positive impact on participants who complete it, with many indicating a high level of satisfaction with the program." The study utilized a range of academically validated measurement scales, including the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI), Brief Resilience Scale (BRCS), Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire-Short Form (FFMQ-SF), Short-Form Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ-SF), Social Connectedness Scale-Revised (SCS-R), Mental Health Inventory-5 (MHI-5), The Active-Empathic Listening Scale (AELS), and the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). In addition to statistical analysis, the research team also conducted interviews and focus groups with participants, as well as program staff. The research design has been developed over several years of analysis of the ICP, which has been offered to inmates in CDCR facilities since 2013. In 2018, Center for Council was asked by the Office of the Inspector General to present its approach to research, which focuses on shifting criminogenic factors like empathy, impulse control and anti-sociality, to the California Rehabilitation Oversight Board. Methodology developed for this research has been referenced in the state's CARE Grant program, enacted into California penal code in July of 2019. The results of the study will be published in an upcoming article. The evaluation report can be viewed here. Sam & Jared with Warden Tammy Foss and the leadership team of the ICP at Salinas Valley State Prison  The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation has awarded Center for Council with new funding as part of the sixth round of its Innovative Programming Grant. This round of funding was intended to support rehabilitative programs with victim-focused restorative justice components that emphasize "offender accountability" and develop insight into the perspective of those harmed by criminal acts. Council is a powerful practice for developing empathy and taking the perspective of "the other," through deep listening and authentic presence. Exploring the perspective of those harmed is an important part of the work of the Inmate Council Program and we are eager to develop this aspect of our program curriculum with this new opportunity. There was enormous interest expressed in this funding opportunity and CDCR received grant proposals amounting to over six million dollars in proposed programming. Only 17% of the proposals submitted were successful. We are grateful for this opportunity to provide our programming at two facilities, the Substance Abuse Treatment Facility, in Corcoran, and Ironwood State Prison. Both programs will operate for two years, and will set the stage for self-sustaining programming, facilitated by inmates who will eventually co-lead the program and who, we hope, will join our efforts to build and support programming for impacted communities upon their release.

It wasn't until a year after getting involved with the Inmate Council Program that I mentioned Council to my family; and that was only because I was invited to speak at Center for Council’s Social Justice Council Project celebration via speakerphone. Before the event all my family knew about Council was that it was a group that I attended on Tuesday nights and that the program was helping me make significant changes in my attitude and my outlook. That event was where my family experienced first-hand exactly what I did each Tuesday night in the Delta Yard Chapel. They got to sit in Council circles; they shared stories about their lives; they learned about The Four Intentions that setup the foundation for the Council practice: speak from the heart, listen from the heart, be spontaneous, be lean of expression. They listened to the stories of other participants sitting in the circle and heard so many similarities to their own narratives. At the end of the day, my family walked away with a better understanding of what it was that I was doing, and they had so many questions for me: “Why didn’t you tell us about this thing that you do?” “Do you know all of these people?” “How do we get involved?” “Can we do Council too?” They didn’t’ know that Center for Council existed outside of the prison setting. From that day forward, in most of the conversations that I had with my wife, Jolene, there was some mention of Council. After witnessing how much Council had changed my outlook and behaviors, and experiencing the joy she felt after engaging with the practice herself, Jolene joined the Trainer Leadership Initiative. And because we both were now involved in the program, we would discuss how we would practice Council with our kids during their visit to Salinas Valley State Prison. Jolene and I were started using Council techniques when we’d talk with each other; we weren’t arguing like we used to. We were actually listening to each other, paying attention to each other, and before we knew it, our marriage improved. We couldn’t wait to have a Council with the kids. When we finally did, it brought our family closer together. Our first Council experience as a family was very emotional. After giving the kids a brief description of what Council is and what we would be doing I then placed some pillows on the floor, arranged in a circle, to sit on. And I even left a place for the empty seat. I put a blanket on the floor for our center and now all we needed was a talking piece. There wasn't much to choose from in that family visiting unit so we settled on my daughter's hairbrush and a NERF football. I then went over our prompt and demonstrated the process of making a dedication. After that, we dropped into Council. The conversation began light and lively, and as we shared our story and our truth we began to carry the conversation deeper. Giving our kids the space to talk honestly about what they were experiencing while I was in prison gave me a better understanding of who they were and what they were going through. I was able to look at them with compassion and empathy and actually understand their perspective. It was amazing to actually HEAR their stories. Sitting in that family visiting unit gave us all the time that we needed to explore and address all the issues that we hadn’t had a chance to talk about. And, because Jolene and I knew how to navigate all the emotions that were coming up, holding this family Council was very restorative. It didn't matter that we were in a family visiting unit, in that moment that space was sacred. We still have Council as a family, and when we can’t sit in the circle because of time or space, we always try to use the Four Intentions as a guide in our everyday conversations. We know how to give each other our full attention.  On April 6, 2018, I was found suitable for parole by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Board of Parole Hearings. The work I had done to transform my perspective and character had paid off. I had no idea that it was after I was granted parole that I would go through the real fire. The last 120 days of my sentence were the hardest, most challenging days of my time in prison. As soon as word got around that I would be out on parole, inmates who had never challenged me before became aggressive toward me. Not because they were bigger or badder than me, but because they knew I had something to lose. They knew that I wouldn’t respond to their advances the way that I would have in the past. It was then, as I was walking away from the insults and the challenges, that I realized that I was, in fact, ready for freedom. In all my years in prison, I had never been tested the way that I was during this time. I surprised even myself when I responded to their challenges with empathy and compassion. Nobody warned me about the anxiety that kicked in as the days turned into weeks and months. When you’re granted parole, there is a review process that can take up to 120 days. Your case goes before a review committee and then goes to the Governor for a final decision. Even though you may be granted parole, the decision is not final until the Governor’s review, or until the 120 days is up. I went from knowing my release date to not knowing. At any point during the review process, the Governor has the power to reverse or affirm the parole board’s decision. And if at any time during the process you get into trouble, that decision could be affected as well. I’ve never had so much hanging over my head. And still, this wasn’t the worst part. The worst part of my last 120 days was the toll that this waiting period began to take on my family. I had been away for approximately 17 years. I had never been physically present in my children’s lives; they were all born while I was incarcerated. The most time that we’ve ever spent together was in a “family visiting” cottage. Our lives were built around me being in prison. So, although we all were very excited about the news that I’d been granted parole, we had no idea what to expect. All we knew was that there were a lot of changes headed our way and the anticipation made it worse; the slow pace of the review process only added fuel to the fire. We caught ourselves arguing over things that we’ve never argued about before. So, there I was, trying to navigate the parole transition period, not doing anything that would jeopardize the parole board’s decision, while at the same time trying to handle family life and the anxiety of moving through all of it. There was a point where I began to feel overwhelmed and I decided to just sit in my cell and stay out of the way. I cut myself off from my routine, from the prison world, and in doing so, from some of the things that had been keeping me going in prison. I began to get agitated, angry, and frustrated that things weren’t moving along at the pace that I hoped or expected they would. I am thankful that I had the practice of Council to help me explore and hold all these emotions and unexpected twists and turns that life was throwing at me. As I was facilitating Council circles during this process, there were stories of patience and perseverance coming from my fellow inmates that helped me cope with the issues I was facing in my own life. If I didn’t have the skills that I had developed in Council—to find comfort in stillness, an ease in the unknowing, and the ability to listen to the stories of others—I believe I wouldn’t have made it through my last 120 days inside. It was in the collective wisdom of the Council circle where I found my strength and peace. It was there in the circle with my brothers where I found my way home.  Before being released from prison, I worried that the world I would be returning to would be a scary place. On my very first day outside, I noticed that most people walking down the sidewalks of LA were looking down at their phone or some type of device that connected them to social media. People didn’t take time to look up and acknowledge one another. Nobody was paying attention to what was going on around them; or next to them; or who was behind them at the checkout line at the grocery store. In prison you learn very quickly to notice EVERYTHING. “Keep your head on a swivel” are words to live by. Paying attention in prison will save your life. Even when you’re on the yard playing sports or chess— your attention is never fully on the game. You’re scanning the yard from end to end as a lifeguard would a swimming pool, looking for signs of danger. If you see someone digging in the dirt it’s likely that he’s burying a weapon or pulling one up. If they’re digging in their waistband it’s likely they’re pulling out a weapon or putting one away. You learn to look for the signs. Most of the time the people you’re watching are watching you watching them; and the correctional officers watch us all. There is a lot of eye contact in prison, acknowledgement of one another. You really feel noticed. It is even a sign of disrespect to walk past someone without taking the time to acknowledge them in some type of way—a nod of the head, a smile, a hand shake, even a simple hello. When I joined the Council program I learned about “reading the field” and paying attention to body language and things that were unsaid. What got me the most is that I had already mastered these skills. So when we learned about mindfulness and paying attention to the present moment without judgement, these teachings only reinforced and put into words what I was already doing. After I became a Council facilitator I was applying these tools in a more positive way, to really benefit myself, and they stayed with me for the course of my time in prison. Council enhanced these skills for me, my awareness of what was happening around me deepened. I was NOTICING more. And the more I noticed about the world around me, the more I noticed about myself. What began as a means of survival became a way of life for a different purpose: the bigger picture, the third consciousness, the reason why we do Council, and that has carried over to the way I interact with the free-world. What I have been encountering out here, though, is that people don’t live by the same rule of thumb: sometimes I get weird looks when I say hello, or good morning. Other times people seem shocked to receive a friendly smile or help from a stranger. But then there are the ones that seem to be as alert as I am. There is a familiar look in their eye; they have the look of someone that has been on a prison yard, having to play by the rules as a means of survival. Usually they can be spotted by the tattoos they wear, their piercing eyes, or the weathered look of someone that has spent a little too much time in the sun. I may not personally know this individual, but with the simple nod of the head we have a connection. It feels good to be seen. Everyday I wake up and I set the intention to acknowledge the world around me in all of its forms. It may be a random stranger that needs to be heard like a guy I met at a gas station that just wanted to congratulate me for having such a beautiful family. He didn’t even know that I was just released from prison only hours before. Or it may be a cashier at a Walmart that wanted to talk about her brother that was released from prison after serving twenty-nine years. Or even a homeless person on the sidewalk that asked me for a cigarette. Or the police officer that helped me find the train station. In all of these encounters we shook hands and introduced ourselves, and walked away with a smile and a sense of humanity. In all of these encounters I walked away feeling refreshed and relieved to find that the world isn’t such a scary place after, all as long as we take the time to see one another.  "I never knew what would come of me joining the Inmate Council Program, but when I saw what it did for me and my family I was convinced that this is something that I want to do for the rest of my life." – Sam Escobar Sam Escobar was introduced to the Council practice during his time in Salinas Valley State Prison. Skeptical of the Inmate Council Program at first, Sam spent many sessions watching other men in the circle speak honestly about their lives, often unearthing emotions and offering up a vulnerability previously unseen within the prison setting. Seeing this unfold within the circle, Sam realized that Council was a space where people would leave their comfort zone, speak openly from the heart, and let their guard down—something that, growing up in gang culture, Sam was vehemently warned against. Sam says he came to see that the authenticity and vulnerability he was experiencing was a result of the unique quality of nonjudgmental listening that the program participants brought to the circle. It took Sam a little while of observing how the group held space and what others were sharing before he was able to get out of his own comfort zone and open up. In a story for ATTN, Sam writes: “For someone who was once involved in street gangs and prison gangs and who participated in race riots and prison stabbings, letting my guard down was a big turnaround. I no longer saw other inmates through the lens of the gang, as the enemy, but as a prospective member of the Council, someone who could fill the symbolic empty seat in the circle. I see them as someone waiting to be heard, listened to, understood with compassion and empathy, potential links in this chain of peace and human kindness.” Over the next few years, Sam became the Chairman of the group and helped expand the program throughout the prison, and even introduced Council to interested officers. Earlier this year, Sam was released on parole. His Parole Commissioner made special note of the transformation Sam had undergone due to his participation in the Inmate Council Program and his leadership of Council circles within the prison community. We are thrilled to welcome Sam back into the Los Angeles community and even more excited to announce that Sam is now an official member of the Center for Council team! As Center for Council’s new Outreach Associate, Sam will help us present future programs to agencies and individuals and work with our team in visioning new program opportunities. We are honored to have him speak about his unique and impactful experience working with Council and how it has the power to transform individual lives just as it did his. In addition, Sam will be lending his voice to our Center for Council narrative, contributing stories and articles about his time transitioning back into the community from prison and how he continues to integrate skills he learned practicing Council in the face of both challenges and new opportunities that arise for him. Keep an eye out for Sam’s stories in the coming weeks!

Just recently, Mathew was released from prison and is reintegrating back into his former community. His story is similar to many inmates who participate in the Center for Council Inmate Council Program. For three years now, Center for Council has provided programs inside prisons across the state of California, teaching inmates to practice and facilitate this work. Council programs have been proven to decrease aggression, heighten one’s sense of empathy and compassion, and help those who participate to find their voice. All of these skills benefit both the individual and the community at-large.

In September Mathew spoke about his experience with Council and how important it was for him to participate in and facilitate Council circles for fellow prisoners. Mathew opened up about the difference between Council and other rehabilitative programs and how, through learning to work with Council and listen and speak from the heart, he was able to experience meaningful rehabilitation.  Randy has been the warden at both Correctional Training Facility and Salinas Valley State Prison, in Soledad, California; he is currently a Commissioner on the Board of Parole Hearings. After learning about the practice of Council and witnessing the transformation and shift in attitudes of the prisoners who participated in the Inmate Council Program, Randy facilitated a circle with his correctional facility staff. It was an informal circle, around a small conference table in his office, but the effect of that single practice was no less profound. In a working environment where being vulnerable is discouraged, where the traumas and stresses that one is exposed to while on the job can be overwhelming, Randy knew how important it was to create a space for his employees to be able to be open and honest. Correctional staff and officers who work within prisons are experiencing very high rates of work-induced anxiety and stress, often resulting in symptoms mimicking those of soldiers returning from war zones. Randy was struck by the openness and candor of his staff during their Council circles. Council provided a space for them to individually and collectively process some of the things they had witnessed on the job, as well as to reconnect with one another in a supportive and uplifting way.

Center for Council is now beginning to work with law enforcement officers, training them in the practice of Council so they will be able to facilitate circles themselves. Council is an adaptable, generative practice, serving all communities and circumstances. Through the transformation of individuals who participate, who share their stories and listen deeply to the stories of others, the entire community can feel the effects of the change. In September, Randy spoke about his experience with Council and how important it was for him to facilitate Council circles for his staff.

Edward encountered Council for the first time at Ironwood State Prison. He was one of the first participants to sign up for the Prison Council Initiative there and became a leader within the group after completing both the Council 1 and Council 2 training workshops offered by Center for Council trainers. Edward was incarcerated for 27 years before being called for an interview this summer before the Board of Parole Hearings. That interview led to the granting of parole and Edward is now in the process of reintegrating himself into the San Diego community. Edward credits the success of his rehabilitation efforts, and the granting of parole, to skills and perspectives he learned in the workshops and practice groups offered by the Prison Council Initiative. When CDCR’s Office of Public Communications arranged for Center for Council to videotape inmate testimonials about the impact of the program, we were struck by Edward’s extraordinarily clear and insightful perspective. His articulation of the power of the work of Council remains a highlight of the short film on the Prison Council Initiative (find the link below). Center for Council caught up again with Edward recently and asked him to share his thoughts on the reentry process and how the practice of Council has helped him transition back into the world outside the prison gates. Edward’s passion and positivity is contagious; it is apparent that he doesn’t take a thing for granted. Center for Council: Edward, could you tell us about your experience in general with Council and what it has meant to you?

Center for Council has recently received word that we have been awarded funding to bring the Inmate Council Program (ICP) to eight more California State prisons. Three of these new sites will be funded for three years of ICP programming. Council is now being practiced and taught within 22 CDCR institutions around the state. The ICP offers council training as a "rehabilitative resource" and teaches inmates how to independently facilitate Council circles on the yard for other inmates. Our preliminary research with RAND Corp and University of California has demonstrated that our Council programs "lead to reduction in anger, aggression and hostility and better communication, cooperation and pro-sociality." And we know that the work is profoundly shifting prison culture in a positive direction. We are thrilled to expand this work and eager to support an ever-growing circle of incarcerated carriers of Council as they find their way into the practice and bring it to others on prison yards around the state. Check out Sam Escobar's powerful and inspiring essay on leading Center for Council's Inmate Council Program at Salinas Valley State Prison, recently published online!

A powerful new website highlights innovative programs at the forefront of prison reform.  Our longtime funder, Kalliopeia Foundation, has created a new website called "Beyond Prison," that highlights the work that Center for Council is doing, along with that of our colleagues at ArtSpring, Insight Garden Program, Insight Out, Mind Body Awareness Project, Prison Mindfulness Institute, and Rehabilitation Through The Arts. We're thrilled to be engaged in this coalition of like-hearted organizations, promoting transformative work in prisons, communities and organizations, and we're grateful for the collaboration and mutual support of this powerful group of organizations. "Beyond Prison" explores innovative approaches to rehabilitation and offers a new vision of what prison could be. Take a moment to read the chapter on Center for Council's Inmate Council Program – as well as the compelling introductions to work that our colleagues and partners are innovating. It's an honor to be collaborating with such powerful allies and exciting to be recognized and celebrated in this moment of innovation. Read the powerful article now.  In October of 2013, Center for Council and Stories Matter Media, with the support of Cal Humanities "Community Stories Project," collaborated on a film project documenting the extraordinary Inmate Council Progam unfolding in Salinas Valley State Prison. Reporter Kenneth Miller followed the film crew into Salinas Valley State Prison and wrote the following article on the powerful weekend. Miller reports, "An aura of earnest spirituality suffuses the practice, but there’s no religious content. Nor is there a specific therapeutic agenda. “Council doesn’t start with the assumption that something’s wrong with you,” says retired warden David Winett, a longtime supporter. In corrections, he observes, the custom is to tell inmates, “What you need is a good talking-to.” Council’s core belief, Winett says, is that what everyone needs is “a good listening-to.” By hearing others deeply, the theory goes, people learn compassion; by being heard, they learn to better understand themselves.  "Within one year, a third of those released from prison are back inside. Within three years, two-thirds have returned to prison. To me that says more about the failure of prisons, parole supervision, and reentry programs than it does about the failure of individuals." -Eddie Ellis, formerly incarcerated founder of the Center for NuLeadership, quoted in The Sun, July 2013 While opinions abound on how to best address the issue of recidivism in our prison system, consensus is growing that we cannot continue with the way things have been. California has one of the highest rates of recidivism in the nation, an issue that has led to Attorney General Kamala Harris announcing a new state initiative, the Division of Recidivism Reduction and Re-Entry, aimed at identifying the best ways to reduce those numbers. The practice of Council addresses some of the Criminogenic Factors identified as key to reducing recidivism. Center for Council has initiated a pilot program, currently underway at Salinas Valley State Prison (SVSP) in Soledad, California, to train inmates in Council. Those participants will then lead other inmates in the practice as many prepare to reenter society. A larger initiative is currently in development, which will expand the program being piloted at SVSP to other prisons and increase our community-based network of partners offering Council groups to the formerly incarcerated in the neighborhoods to which they will be returning.  The California Office of the Inspector General released a highly critical report late last week on the deeply dysfunctional culture at High Desert State Prison. Included in the OIG's "Findings and Recommendations," among other efforts to shift the culture for officers and inmates, is implementation of Center for Council's proposal, in partnership with Center for Mindfulness on Corrections, for a council-based wellness and resiliency program for Correctional Officers. Read the full report here  "There are such extraordinary moments emerging in many of these compassion-based programs in prisons and communities. In this season of abundance and thanksgiving, I am reminded of an amazing and moving council I got to participate in at Lancaster State Prison with a group of inmates who had such incredible stories about food. One shared that he has spent decades wondering about pomegranates... so curious about their taste and feel, and their prevalence in mythology and poetry, and his longing to know a pomegranate, and his realization that a sentence of "life without the chance of parole" meant he's probably never get to taste one. "That night, as I walked past a large stack of them at Whole Foods, I felt my heart race. Was it mine to sneak one in next time? Should I petition the authorities to allow it? Or take a picture? Or maybe just to bear witness to the longing and so deeply appreciate my life and the profound teaching these incarcerated elders have for all of us about memory, meaning, longing, grief and renewal...?

"This is such meaningful, sacred work and there is so much of value to be done to integrate folks who are for the most part invisible behind so many concrete walls. These are sons and daughters, in many cases moms and dads, poets and athletes, artists and nerds, violent bullies and kindhearted friends. Many have been there for decades - some are far different men from the knuckleheads who did something stupid years ago. And most of us just chose not to think about it. I think how we regard and make sense of all this says so much about who we are. Sharing these stories creates such intimacy with the suffering, the longing, the compassion, the humanity of our fellow community members. "These stories open our hearts and shift the way we view the system. When we bear witness to these stories we are changed, profoundly. We get to really feel the impact of a dysfunctional system that has real consequence on real people. And it's about all of us..." |

Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

|

|

About |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed